In this article:

When to use Russian preposition “V” and when to use “NA”?

Russian prepositions v and na (“в” and “на”) are challenging for many foreigners studying Russian.

The main difficulty in using prepositions “в” and “на” lies in a large number of exceptions. Please also note that specific applications often evolved historically, therefore it is impossible to go solely “by the rules”.

In languages where the case system still exists, the propositional case would correspond to / or be named Locative, needless to say, this case serves to express a location.

Find our extensive article about Russian cases and conjugation tables here.

Differences between “В” and “На”

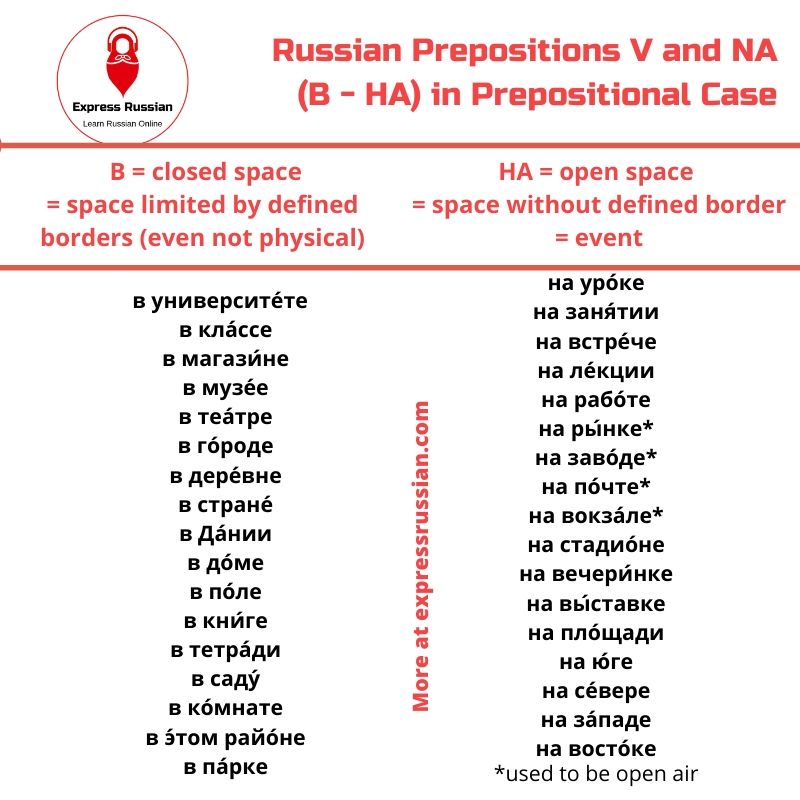

Most of the time, Russian prepositions V “в” and NA “на” when used in Prepositional case, mean the following:

“В” = “внутри” (inside), English analogue “in”, “inside”.

“На” = “на поверхности” (on the surface), English analogue “on”.

You can quickly grasp the difference from these simple examples:

положить в комод (внутрь комода) = put into the chest of drawers (inside)

vs

положить на комод (на поверхность комода) = put on the chest of drawers (on the surface).

However, there are plenty of situations when it is not so easy to figure out whether to use “в” and “на”, especially when analog English expressions are using the preposition “in”. The latter is especially true if the noun you are using the preposition with is non-physical. In this case, one needs to use a bit of imagination and develop his Russian language sense.

The use of the preposition “в” (“in”) with the meaning of location is associated with the idea of limited space, in the absence of limited space – use the preposition “на” (“on”, “at”).

Related: Self-Paced Course “Russian For Beginners”

Let’s see the use of “В” and “На” on concrete examples

Compare Russian prepositions V and NA:

машины стояли во дворе (окруженное забором или домами пространство) –

cars stood in the yard (a space surrounded by a fence or houses)

vs

дети играли на дворе (вне дома) –

children were playing in the yard (outside of home);

выступить на совещании (speak at a meeting) – here, imagine the meeting as a gathering to exchange ideas, an event

vs

принять участие в совещании (take part in a meeting) – here, imagine the meeting as a set of participants grouped within a space.

Or another example: купить в магазине (to buy in a shop, inside a building)

vs

и купить на рынке (to buy on the market, on the open space).

In some cases, the constructions with both Russian prepositions V and NA (“в” and “на”) are synonymous, having only a slight nuance in the meaning.

For example:

работать в огороде = работать на огороде

ехать в поезде = ехать на поезде

слёзы в глазах = слёзы на глазах.

But first things first: let’s discover the basic principles – which of the prepositions to use in various situations.

Russian Preposition V in Prepositional Case is used:

– with all continents and with most countries:

в Европе (in Europe)

в Америке (in America)

в Азии (in Asia)

в Африке (in Africa)

в России (in Russia)

в Германии (in Germany)

в США (in the USA)

в Италии (in Italy)

в Украине (in Ukraine)*

* What is the correct В УКРАИНЕ or НА УКРАИНЕ?

The correct way to say is – В УКРАИНЕ.

With administrative and geographical names, preposition B should be used, for example:

в городе, в районе, в области, в республике, в Сибири, в Белоруссии, в Закавказье

(in a city, in a district, in a region, in a republic, in Siberia, in Belarus, in Transcaucasia).

As a matter of fact, the combination НА УКРАИНЕ appeared under the influence of the Ukrainian language itself, where parts of the country (aka cultural regions, surrounding areas, metropolitan areas), which are not defined by borders, are used with preposition HA, for example, на Полтавщине, на Буковине, на Донбасе (in the Poltava region, in Bukovina, in Donbass region). When Ukraine used to be a part of the Soviet Union, in the Ukrainian language one could say НА УКРАИНЕ and then it was borrowed into Russian. But now that Ukraine is an independent country, the only correct way to say is – В УКРАИНЕ.

Likewise, a lot of English speakers say “in THE Ukraine” which is also wrong, because in English there is no definite article before the countries’ names, however, there is a definite article when speaking about some regions, outskirts, geographical areas. I think the root of this mistake is the same. Ukraine used to be “a part” of something else.

Related:

Best Online Tools to learn Russian

– with cities, villages, and other administrative regions:

в городе (in the city)

в стране (in the country)

в районе (in the neighbourhood)

в деревне (in the village)

в области (in the region)

в республике (in the republic)

в Сибири (in Siberia)

в Западной Сибири (in Western Siberia)

в Белоруссии (in Belarus)

в Закавказье (in Transcaucasia)

в Москве (in Moscow)

в Берлине (in Berlin)

в Париже (in Paris)

в Лондоне (in London)

в Московской области (in Moscow Region)

в Чечне (in Chechnya)

в штате Айова (in Iowa)

в провинции Британская Колумбия (in the province of British Columbia)

в графстве Эссекс (in the county of Essex)

в земле Бавария (in the state of Bavaria)

– with houses and in most other enclosed spaces, inside something:

в доме (in a house)

в квартире (in an apartment)

в комнате (in a room)

в стакане (in a glass)

в шкафу (in a closet)

в парке (in a park)

в саду (in a garden)

Exceptions:

на Родине (in the homeland)

на вокзале (at the train station)

на складе (at the warehouse)

на фабрике, на заводе (at the factory)

на этаже (on the floor)

на кухне (in the kitchen)

– with educational institutions, banks, organizations, offices, and cultural institutions (this also relates to the notion of a closed space):

в институте (at the institute)

в университете (at the university)

в школе (at school)

в аудитории (in the auditorium)

в бюро путешествий (at the travel agency)

в министерстве (in the ministry)

в музее (in the museum)

в театре (in the theatre)

в кино (in the cinema)

в парке (in the park)

в цирке (in the circus)

– with different groups of people:

в классе (in the class)

в группе (in the group)

в отделе (in the department)

в бухгалтерии (in the accounting department)

в администрации (in the administration)

в правительстве (in the government)

в парламенте (in the parliament)

– when speaking about water bodies (something being in water):

В реке плавает рыба (There is a fish in the river)

Мы купаемся в озере (We are swimming in the lake)

Russian Preposition HA in Prepositional Case is used:

– if one object is clearly located on the surface of another and this surface appears to be something open, not limited from above:

на улице (on the street)

на мосту (on the bridge)

на берегу (on the bank)

на остановке (at the bus stop)

на площади (at the square)

на балконе (on the balcony)

на стадионе (at the stadium)

на рынке (at the market)

на стуле (on the chair)

на диване (on the sofa)

на столе (on the table)

на тарелке (on the plate)

на горе (on the mountain)

на острове (on the island)

– with cardinal points of the compass:

на севере (in the north)

на юге (in the south)

на западе (in the west)

на востоке (in the east)

на северо-западе (in the northwest)

на юго-востоке (in the southeast)

– with the names of mountain regions (meaning mountainous terrain without well-defined boundaries):

на Алтае (in Altai region)

на Кавказе (in the Caucasus region)

на Урале (in the Ural region)

But: в Крыму – in the Crimea

Must be remembered: in Russian, the use of the preposition V (В) with the names of mountains in the plural gives these combinations different meanings – “in the mountain range, among the mountains”:

в Альпах (in the Alps)

в Андах (in the Andes)

в Апеннинах (in the Apennines)

в Пиренеях (in the Pyrenees)

– with islands, river banks, and seashores:

на острове (on the island)

на Кубе (in Cuba)

на Ямайке (in Jamaica)

на Филиппинах (in the Philippines)

на Гавайских островах (in Hawaii)

отдыхать на Черном море (to have a vacation on the Black Sea)

NOTE:

Самара находится на Волге (Samara is situated on the Volga (on the banks of river Volga)

In comparison,

В Волге раньше было больше рыбы (There used to be more fish in the Volga (inside)

– with streets, squares, and other open horizontal spaces:

на улице Пушкина (on Pushkin street)

на проспекте Героев Сталинграда (on Heroes of Stalingrad Avenue)

на Бродвее (on Broadway)

на Елисейских Полях (on the Champs Elysees)

на площади Свободы (on Freedom Square)

на Театральной площади (on Theater Square)

на стадионе (at the stadium)

на футбольном поле (at the football pitch)

на втором этаже (on the second floor)

на пляже (on the beach)

– with faculties, academic courses, and parts of the educational institutions:

на филологическом факультете (at the philological department)

на романском отделении (at the Roman languages department)

на втором курсе (in the second year)

на курсе русского языка для иностранцев (at the Russian for foreigners’ course)

на кафедре русского языка (at the department of the Russian language)

– when speaking about means of transport:

ехать на автобусе / на поезде / на машине / на трамвае / на метро (go by bus/ train / car / tram / metro)

плыть на пароходе (swim by ferry)

лететь на самолете (travel by plane)

But:

В автобусе было жарко (It was hot in the bus) – inside

Мы ждали в машине (We waited in the car) – inside

Я обедал в самолёте (I had lunch on the plane) – inside

– when speaking about an event:

на уроке (at the lesson)

на опере (at the opera)

на выставке (at the exhibition)

на спектакле (at the show)

на балете (at the ballet)

на концерте (at the concert)

We can also say “в опере” but then the word “опера” will switch its category from an event to a building with a roof and a door, so it will mean “in the opera building”.

Exceptions:

в путешествии (in the journey)

в поездке (in the trip)

в дороге (on the road)

в отпуске (on vacation)

в командировке (on a business trip)

в кино (in the cinema)

в театре (in the theatre)

в цирке (in the circus)

– In expressions на почте (at the post office), на заводе / на фабрике (at the factory), на вокзале (at the train station), because historically the notions of “post”, “factory”, “station” were not associated with the idea of a closed building.

In the framework of this article, we cannot mention absolutely all the exceptions related to the use of prepositions “в” and “на”, and you may come across others that you just need to remember.

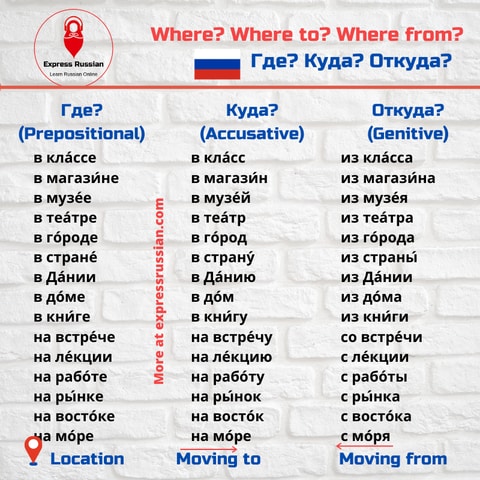

Russian Prepositions V and NA (В – НА) in Accusative Case

As you just learned, prepositions “в” and “на” can be used with Prepositional case (with the question “where?”, speaking about location).

Likewise, they can be used with Accusative case (with the question “where to?”, speaking about direction, moving towards):

Я был на почте (Prepositional) – Я иду на почту (Accusative)

I was at the post office – I am going to the post office.

Я живу в Берлине (Prepositional)– Я еду в Берлин (Accusative)

I live in Berlin – I am going to Berlin.

Я живу на улице Пушкина (Prepositional) – Я вышел на улицу Пушкина (Accusative)

I live on the Pushkin Street – I went out to the Pushkin street.

Summary

As you see from the examples above, the meaning of the sentences and the cases are different, however, we use the same prepositions.

Find more examples of Russian prepositions with pictures on our Instagram

And lastly, please remember:

When used either in Accusative or Prepositional case, Russian prepositions V and Na have the following opposite pairs (antonyms):

в – из, на – с:

Иван поехал на Кавказ – Иван вернулся с Кавказа

Ivan went to the Caucasus mountains – Ivan came back from the Caucasus.

Иван поехал в Крым – Иван вернулся из Крыма.

Ivan went to the Crimea – Ivan came back from the Crimea.

Я еду в Германию – Я еду из Германии.

I am going to Germany – I am coming back from Germany.

Я вошел в комнату – Я вышел из комнаты.

I came into the room – I came out of the room.

Я иду на работу – Я иду с работы

I am going to work – I am returning from work.

Я был на концерте – Я пришел с концерта

I was at a concert – I came back from a concert

I hope it became more clear to you when to use Russian prepositions

v and na (“в” – “на”) in Prepositional Case.

If you have questions, please write them in the comments below.

As you have seen, Russian prepositions V and NA, and others are very much related to Russian cases they are used with.

Do you want to learn Russian cases once and for good?